In 1857, Dred Scott versus Sanford was decided by the Supreme Court in America. Mr. Scott was an African American who resided in Illinois (free state) from 1833 to 1843. Upon returning to Missouri (slavery state), Scott sued for his freedom claiming that because his original residence is from Illinois, a free state, he should be perceived as free even in a pro-slave state like Missouri. The Supreme Court ruled that no one but a citizen of the United States could be a citizen of a state, and that only Congress could confer national citizenship. Since no person descended from an American slave had ever been a citizen, it goes without saying that Mr. Scott’s argument was rejected. However, in just a few years the US Government would legislatively overturn this ruling by passing the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution following the Civil War.

13th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution

Section 1 of the 13th Amendment reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”[1] It’s worth nothing that the 13th Amendment does not completely outlaw slavery. It allows for slavery as a form of punishment. The government can still force slavery on a person provided it is in light of a legal punishment for crimes committed against the state, as defined by the state.

The text of the 14th Amendment reads, “Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” (emphasis mine).[2] The 14th Amendment introduces the “equal protection” language into American discourse. This is important to note, as “equality” becomes a driving sociological understanding of the American civil and political discourse. While one can argue that equality language is embedded in the foundational document of the United States, the Constitution, as the Supreme Court has done with multiple rulings, that means one must reinterpret what the original authors meant for it to include any of the classes of people it now includes – African Americans, Latina/o, women, LGBTQ, etc.

Provided you had a court proceeding, then it is completely legal for you to be deprived of life, liberty and/or property subsequent to the ruling.

Again, it is worth noting that according to the 14th amendment your rights can be deprived if you’ve had “due process.” Provided you had a court proceeding, then it is completely legal for you to be deprived of life, liberty and/or property subsequent to the ruling. However, this then raises a host of sociological problems: how is due process applied? Who writes the laws? Who enforces the laws? Who interprets the laws? Who levies the judgement? Who enforces the judgement? Who maintains accountability throughout these processes? These questions form the foundation of the following sections.

Homer Plessy v Fergusson 1896

In 1891 a group of Creole professionals from New Orleans banded together to form the Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. As the name implies, the group’s purpose sought to bring a legal case to trial for Louisiana’s 1890 law that restricts train car seating based on a person’s race. The statue of Louisiana required “railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches…to provide equal, but separate, accommodations for the white and colored races…and providing that no person shall be permitted to occupy seats in coaches other than the ones assigned to them, on account of the race they belong to.”[3] Homer Plessy, the group thought, was an ideal person to form the case around because he was seven-eighths white and one-eighth black. Because of his mixed ethnicity how could the law possibly adhere to the 14th amendment of equal protection. If they forced him to sit in the black car his majority whiteness was not given the equality allegedly afforded by the 14th amendment and vice versa.

Louisiana’s law was upheld 7-1 by the Supreme Court. In writing for the majority opinion, Henry Billings Brown, argued that the 14th amendment was only intended to secure the legal rights of African Americans, not the socialrights. He further argued that separating the car’s passengers did not re-establish any form of servitude, and therefore, did not violate the 13th amendment. Justice Brown wrote, “The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races unsatisfactory to either. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.”[4] This argument effectively institutionalized the Jim Crow Laws in the Southern portion of America, in what became known as “separate-but-equal.” Essentially the argument goes that segregation does not, in and of itself, constitute unlawful discrimination. The notion of separate-but-equal would stand for 63 years, or about two and a half generations, before the concept of segregation would be deemed unlawful.

1954 Clifford Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

On May 17, 1954 the Supreme court ruled against the Topeka Board of Education. The Supreme Court merged together four separate cases that had made their way through the state and district courts. All of them shared a similar storyline: “African American minors who had been denied admittance to certain public schools based on laws allowing public segregation by race.”[5] This was a direct challenge to the 1896 Plessy v Ferguson case establishing the notion of separate-but-equal, as well as a claim that segregation is a violation of the 14th amendment.

Yet, because of school segregation, the schools were separate and radically unequal. The white schools had better facilities, better teachers, better food, better busing systems, and better sports programs. In virtually every way a school could be compared, the whites-only school was superior. There was no equality, only segregation.

In a rare show of solidarity, the US Supreme Court ruled unanimously. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the unanimous opinion and stated that the notion of “separate-but-equal” is fundamentally unconstitutional and violates the 14th amendments Equal Protection Clause. The Court also argued that the segregation of schools based on race “instilled a sense of inferiority that had a detrimental effect on the education and personal growth of African American children.”[6]

Dallas Independent School District

DISD can trace its roots back to June 16th of 1884. That date represents the beginning of the Dallas public school system which featured four white schools, and two black schools. According to the best estimates of census data (which was largely damaged in a 1921 fire in D.C.’s Commerce Building) Dallas’ population was between 35,000-40,000 people at this time.[7] By 1892 the Dallas Colored High School opens, which is the only high school that students of color are legally allowed to attend. In 1922 the school’s name is changed to Booker T. Washington. DISD continues over the next 60 years to promulgate, codify, and institutionalize two distinct schooling systems (to say nothing of Highland Park’s separation from DISD and incorporation in 1914 which promoted a white’s only policy that lasted a full ten years after the 1954 Brown v Education ruling, which is longer than even DISD desegregation approach, and which merits only two sentences in HPISD’s official public historical narrative).[8]

As the Fall of 1954 came, Dallas dug its heels in against the perceived federal overreach of the Supreme Court decision earlier that same year. Dallas Times Herald on September 2, 1954, quoted then DISD superintendent Dr. W.T. White[9] as saying that Dallas public schools “definitely will not end segregation…(1) The opinion of the Supreme Court announced May 17 (1954) was one of philosophy and policy and not a directive or a decree directing that segregation be done, and (2) The schools of Texas are operated under the laws enacted by the Legislature pursuant to the Constitution. In Texas, the Constitution prescribes segregation.”[10] According to the Herald, “The superintendent said local school boards ‘have no option except to carry on the legally constituted segregated schools as presently organized.’”[11]

In case it be misconstrued that the DISD Superintendent was somehow fighting popular opinion, it should be noted that, “In general, the majority population of Dallas was against early plans for desegregation—in a city-wide election, Dallasites voted four to one against school integration. As well, DISD and powerful business interests sought to stifle the various lawsuits that ensued.”[12] The city of Dallas, its residents, politicians, businesses, and churches had little interest in accommodating poor black students. Besides, many Dallasistes would argue, blacks were freed from slavery nearly a hundred years ago, and they still had not achieved any sort of economic independence or social status, save for a few exceptional folks along the way. Why should the city facilitate helping a group of students who do not want to help themselves?

In the following year, 1955, in an updated ruling from the Supreme Court on Brown, commonly called Brown II, the court implores states to adopt desegregation efforts “with all deliberate speed.”[13] But deliberate speed is in the eye of the beholder, or in Dallas’ case, completely irrelevant because Texas law prescribes segregation, and that’s the highest law Texans recognize (Don’t Tread on Me, comes to mind here). Over the next five years, DISD would repeatedly visit the courtroom of US District Court Judge William H. Atwell. Judge Atwell continually sided in favor of DISD’s exclusionary school system. In 1955 Judge Atwell ruled against a plaintiff seeking desegregation plans for DISD. Again in 1957, Judge Atwell ruled against the NAACP fighting on behalf of two black students who wanted to attend a nearby white-only school.

By 1961, Dallas is the largest city in the South, and the last in Texas, still maintaining a segregated school system.[14] The courts pressure begins to push DISD towards integration. Yet, Dallasites often cited the 1957 desegregation effort in Little Rock, Arkansas, known as the Little Rock Nine, as a reason for its slow approach. With Judge Atwell retiring, the court case moved to Judge T. Whitfield Davidson, himself a staunch segregationist, of the Fifth Circuit Court, to implement desegregation.[15] In 1961 DISD begins to implement their “Stair-step Plan,” modeled after a similar plan used in Nashville, Tennessee for desegregation. On September 6, 1961 eighteen African American students would be the first to enter white-only schools. Just six years later, in 1967, DISD would declare Dallas schools desegregated.[16]

Tasby v Estes

While DISD believed it had complied with the Brown ruling from 1954, by 1970 Sam Tasby disagreed. Mr. Tasby lived near Love Field and questioned why he had to send his two black children several miles to an all-black school when there was a perfectly fine school within walking distance of his house, but the school happened to be white. On October 6, 1970 Mr. Tasby filed a lawsuit against DISD claiming that the school district continued to operate a dual school system, a segregated system, which is prohibited under Brown. This challenge from Mr. Tasby would wind its way through the courts off and on over the next 33 years.

Sylvia Demarest,[17] who served as Mr. Tasby’s attorney, commented to KERA, “What we found was truly astonishing, because in almost all cases, the changes in school boundary zones preceded what was called at that time blockbusting – white flight – in that what the maps showed was that the school district would rezone a black school not to create an appropriate mix of students, but to include a white block that would then have to send their kids to an all-black school. And what would happen, there’d be absolute panic; houses would be sold, a lot of times for far under market value.”[18]

In July 1971, US District Judge William M. Taylor agreed with Tasby saying that “a dual system still exists.”[19] From there Judge Taylor mandated that DISD present another plan to, once again, desegregate the school system. Shortly after, on July 23, 1971, DISD published the “Confluence of Cultures Desegregation Plan” as their next step to dismantle a systemically segregated system.[20] By 1975, the Fifth Circuit Court rejected parts of this plan and ordered DISD to come up with a new one.[21] This process would repeat several more times with DISD continuing to fight in court any and all attempts at moving towards desegregation across its schooling system.

Nearly thirty years after the Brown v Board of Education ruling, in August of 1983, “the DISD school board finally ended its fight against court-ordered desegregation by unanimously accepting the Fifth Circuit’s upholding of Judge Sander’s desegregation plan. And from that time on, DISD would remain under Sander’s oversight until he declared it desegregated.”[22] However, that declaration would not come until 2003, when Judge Sander’s officially ruled DISD desegregated.

Conclusion

“Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.”

Paulo freire

A quote commonly sourced to Albert Einstein, “The world is too dangerous to live in, not because of the people who do evil, but because of the people who sit and let it happen.” In the saga of DISD desegregating its school system, it appears that many people were complicit, not necessarily in promoting or advocating for an explicitly racist system, though there are plenty of those people within the DISD’s narrative, but in the largely unheard and unspoken support of the status quo. As historian, playwright, and social activist Howard Zinn noted directly in the title of his 2004 book, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.[23] Neutrality means you’re still going with the status quo. Those who are silent continue to support and perpetuate the current system as-it-is. Maintaining the status quo is also a privilege. This privilege is rarely seen and described only in terms of “well…that’s the way it is” when, primarily, the system is working for you. If the system is actively disadvantaging you, then you are likely more motivated to change it, whenever possible.

The individualism that we display in America, saying “that’s not me,” or “I didn’t personally harm you” attempts to distance oneself from the group (also noted by the hashtags such as #NotAllWhitePeople or #NotAllMen, it’s a perch of privilege to be able to individualize oneself from the collective whole. Instead of realizing the ways in which you, individually, actually contribute or are complicit with the problem). In this distancing, the goal is to appear neutral. Yet, as Paulo Freire wrote, “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.”[24]

The story of DISD is intertwined with complicit people desiring to stay “neutral,” as well as actively racist people looking to maintain a system of inequality to perpetuate their own power. As Dr. Glenn Linden, SMU Professor Emeritus of History summarized in his book, Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades In the Federal Courtswritten in 1995,

In the following forty years, school desegregation continued to be a major problem for the citizens of Dallas. The official response to the continuing federal demands for desegregation had all the classic ingredients associated with school desegregation across the country—resistance by the controlling class and the use of all legal means to maintain segregated schools; disruption and strife between whites and racial minorities; a divided board controlled by whites which continued to operate a dual school system as long as possible; court ordered busing and the refusal of many whites to obey the order; and conflicts within the black community over the final desegregation plan. In many important ways the Dallas story resembles desegregation efforts in other American cities—Houston, Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, and Philadelphia. Each had substantial white flight, problems in recruiting enough minority teachers, a reluctance to admit the degree of racism in the system, and resistance by the white power structure.[25]

This history of DISD is eye opening. The systemic nature of perpetuating injustice through legislated segregation, and through court battles while maintaining the status quo for decades, points to a history that Dallas is still trying to crawl out from under. These historical inequalities have not magically vanished even if Judge Sanders declared DISD desegregated 49 years after Brown v Board![26] What about the thousands, or hundreds of thousands, of children who went through DISD from 1954-2003? What type of education did they get? How did/does that impact their future? What reparation do they get for going through an unequal and unjust system? Simply based on a where a child is born can determine so much of their future within the Dallas educational system! This systemic historical aspect continues to shape Dallas, and its citizens. As Martin Luther King, Jr noted, “We are not makers of history. We are made by history.” This investigation helped open my eyes to further realize that silence is as much an action as protest. Doing nothing is still doing something, and that is unconscionable when lives hang in the balance.

[1] “Primary Documents in American History.” 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress). Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/13thamendment.html

[2] “Primary Documents in American History.” 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress). Accessed April 13, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/14thamendment.html

[3] “Plessy V. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)”, Justia Law, last modified 2018, accessed March 30, 2018, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/163/537/

[4] “History – Brown V. Board Of Education Re-Enactment.” United States Courts. Last modified 2018. Accessed March 30, 2018. http://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/history-brown-v-board-education-re-enactment. See also: “Plessy v Ferguson.” Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/163us537

[5] “Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1).” Oyez. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483

[6] Ibid.

[7] “United States Census Bureau –Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places In The United States: 1790 to 1990. https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/1998/demo/POP-twps0027.html (accessed March 30, 2018).

[8] “History & Traditions: More than 100 years of tradition and excellence in Highland Park ISD. https://www.hpisd.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=924382&type=d&pREC_ID=1260104 (accessed March 30, 2018).

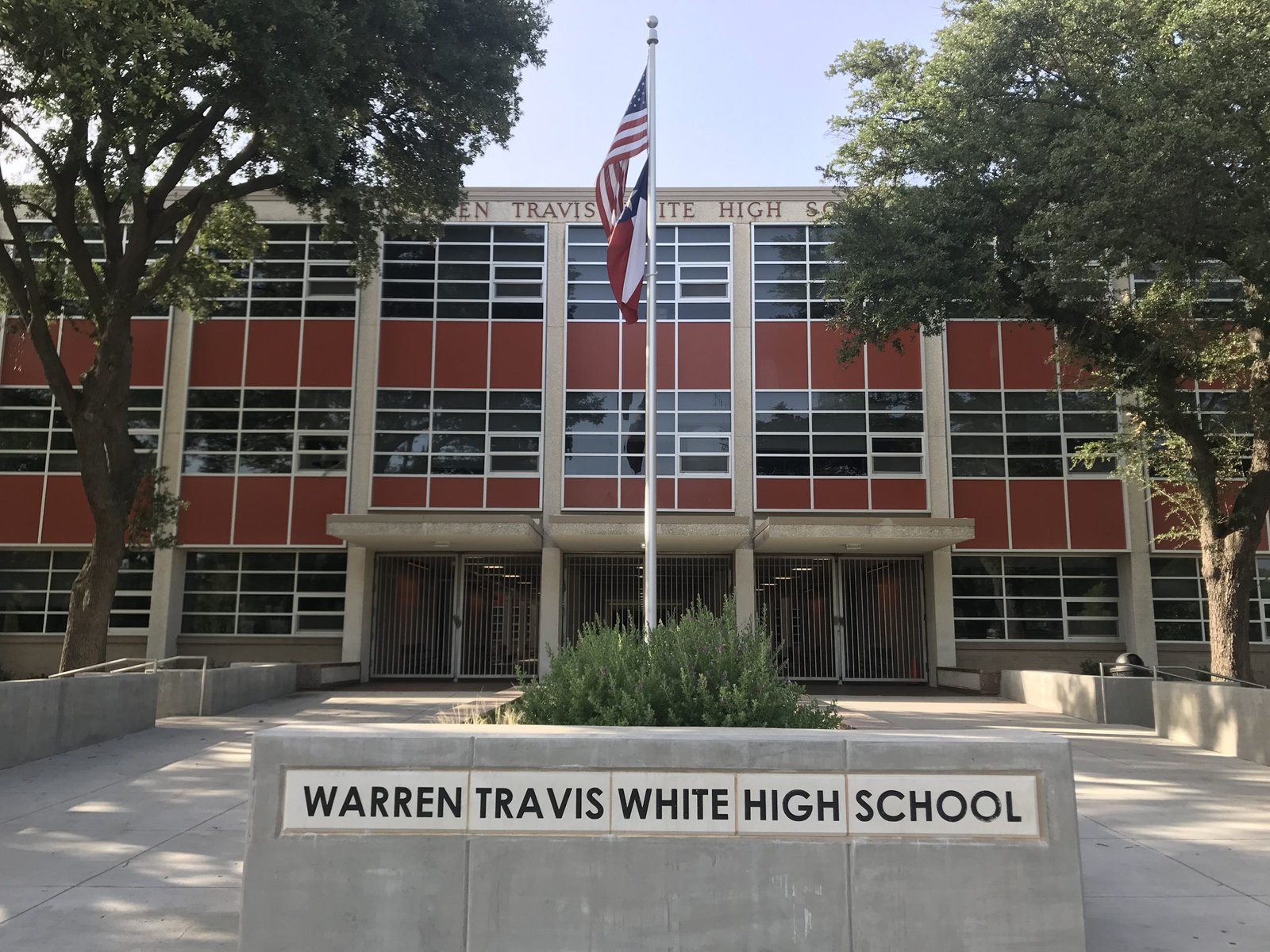

[9] W.T. White would also get a school named in his honor. W.T. White High School (mascot, the Longhorns) is located at 4505 Ridgeside Dr, Dallas, TX 75244 in northwest Dallas near I-635 and the Dallas North Tollway – https://www.dallasisd.org/Domain/664. The official DISD page commemorating Dr. White, ironically titled “Just The Facts,” only notes that “He oversaw construction of 106 new schools, the expansion of 91 and the early years of desegregation, which began in 1961” – https://www.dallasisd.org/Page/16373. Conveniently, it leaves aside his sordid history with human rights pertaining to ethnicity.

[10] School Desegregation: Marion Butts Collection. https://dallaslibrary2.org/mbutts/assets/lessons/L12-civil+rights/Marion%20Butts%20-%20School%20Desegregation(PPT).pdf (accessed March 2, 2018).

[11] Ibid. Additionally, this language from Dr. White seems very similar to what Democratic Governor of Alabama George Wallace would say during his inauguration on January 14, 1963, “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” ‘The feet of tyranny’ spoken of here was Wallace’s attempt to frame the efforts of desegregation by the federal government as oppressive and in violation of the citizen’s and state of Alabama. This helped cast a narrative of big, bad Uncle Sam coming to impose its will on all of the South (harkening back to the Civil War, or “The Lost Cause” as some have come to call it, in order to cast the Confederacy in a heroic light, fighting against long odds, and with a noble mission at heart) and, more specifically, on Alabama.

[12] Underwood Law Library: DISD Desegregation Litigation Archives – Background Info, http://library.law.smu.edu/Collections/DISD/Background-Info (accessed March 2, 2018).

[13] Lakewood Advocate Magazine. 40 years of DISD desegregation. https://lakewood.advocatemag.com/2011/07/22/a-gray-matter/(accessed March 22, 2018).

[14] The caveat here being how you understand and classify Highland Park – village, town, or city. Technically Highland Park is considered a “town” whereas, Dallas is considered a city.

[15] Linden, Glenn. Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts, 1995.

[16] Underwood Law Library: DISD Desegregation Litigation Archives – Background Info, http://library.law.smu.edu/Collections/DISD/Background-Info (accessed March 2, 2018).

[17] Licensed to practice law in Texas since 1969, graduated from the University of Texas, and currently operates a personal injury law office from 1812 Atlantic St, Dallas, TX, 75208. She was also involved in successfully suing the The Roman Catholic Diocese of Dallas in 1997 for its cover up of a priest’s abuse of 11 altar boys – http://articles.latimes.com/1997/jul/25/news/mn-16213

[18] Bill Zeeble, Dallas’ History of School Desegregation, http://keranews.org/post/dallas-history-school-desegregation, accessed March 3, 2018.

[19] Underwood Law Library: DISD Desegregation Litigation Archives – Background Info, http://library.law.smu.edu/Collections/DISD/Background-Info (accessed March 2, 2018).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Zinn, H. (2018). You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train. Beacon Press. https://www.amazon.com/You-Cant-Neutral-Moving-Train/dp/0807071277/

[24] Feire, Paulo. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. 1985, pg 122. https://books.google.com/books?id=TvzK9uKs4CIC&pg=PA122

[25] Linden, Glenn. Desegregating Schools in Dallas: Four Decades in the Federal Courts, 1995, pg. viii and ix.

[26] A study by UCLA Civil Rights Projects finds that most all of the gains from the 1954 Brown v Board decision have eroded with schools have “lost all of the additional progress made after 1967.” (https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/news/press-releases/2014-press-releases/ucla-report-finds-changing-u.s.-demographics-transform-school-segregation-landscape-60-years-after-brown-v-board-of-education)

Subscribe the Newsletter